I was surprised to read that San Jose approved a fee program allowing their Fire Department to charge people for medical treatment. Starting January 1, 2026, a new “first responder fee” of $427 will be charged for medical services provided by the fire department.

What are “First Responder Fees”?

The mayor said, “Our fire department is responding to more and more medical calls where they are performing health care services, medical services, out in the field. […] All we are saying is for the sustainability of our department we need to be able to bill insurance when it is available to collect or recover the cost of providing medical care out in the field.” Approximately two-thirds of the department’s calls involve medical care, or more than 68,000 requests in 2024. The fees are expected to raise $4 million dollars for the San Jose Fire Department.

San Jose’s Mayor told residents that the city would not attempt to collect the money from them, only from insurance companies. “We are not sending debt collectors, it is not going to ding your credit, we are not interested in collecting directly from residents.” Uninsured residents can pay a reduced fee or get the fee waived altogether if they qualify for the “compassionate billing” provision.

California’s legislature first allowed cities to charge “First Responder Fees” in the 1990s. More than 20 California cities are charging the fees, including Napa, Alameda, Vallejo, and San Francisco, which charges $567. In 2014, the Burbank Fire Department started charging $100 when fire personnel respond to emergency medical calls that don’t include transporting someone to the hospital. A trip to the hospital costs between $1,100 and $1,500. The fee “was derived by calculating personnel costs for a typical response, which generally lasts 20 minutes and includes a fire captain, engineer, two firefighters and two paramedics.” Burbank residents can avoid the fee by paying an extra $48 on top of the taxes they pay to fund the fire department.

“First Responder Fees” Are an Abdication of Government’s Responsibility to Provide Fundamental Services

Mariel Garza argued persuasively in the Los Angeles Times that these fees are “a backward response to changing duties of urban fire departments.” Using her common sense, Garza pointed out that charging a fee for calling 911 would lead to less people calling 911, even though this is a service that people are already paying for with their taxes.

Garza’s argument is supported by real-world examples. Linda Grow’s elderly father fell, cracked four ribs, and collapsed his lung. She called 911 to get help for him. Then she got a bill from the Vallejo Fire Department for $1,880. “I want to warn you all it is not a free call and they do not tell you — you just … get this great big bill in the mail at a real bad time … it was free before our city council voted it in. I thought the firemen came out to help if you fell.”

Hundreds of years ago, fire departments were mostly private. Homeowners would pay a fee to an insurance company, and in return, the company would send firefighters only if the house had a “fire mark” indicating it was insured by them. If you didn’t pay the fee, too bad, your house would burn down. This led to the absurd situation where rival fire companies would race to fires to get the insurance payout, sometimes even fighting each other for the money rather than putting out the fire. And poorer neighborhoods were left with no protection. This situation lead to public outrage, and led to advocacy for better fire services by many people, including Benjamin Franklin. Cities began organizing municipal fire departments at the end of the 19th Century. They recognized that fire protection benefited the whole community.

“First Responder” fees are a return to the “pay for protection” model that public departments were supposed to replace. They create a two-tier system: one for those who can afford to absorb the cost and another for those who hesitate to call for help out of fear of the bill. They revive, in modern form, the exact conditions that public fire departments were created to end — a world where lifesaving services are transactional, conditional, and selective.

The public already pays for fire and emergency services through taxes. Adding additional fees at the moment of crisis is a form of double billing that shifts public safety from a guaranteed public good to an optional, purchasable service. It undermines the very idea of emergency response as a shared social obligation and moves us backward to the days when help came only if you could pay.

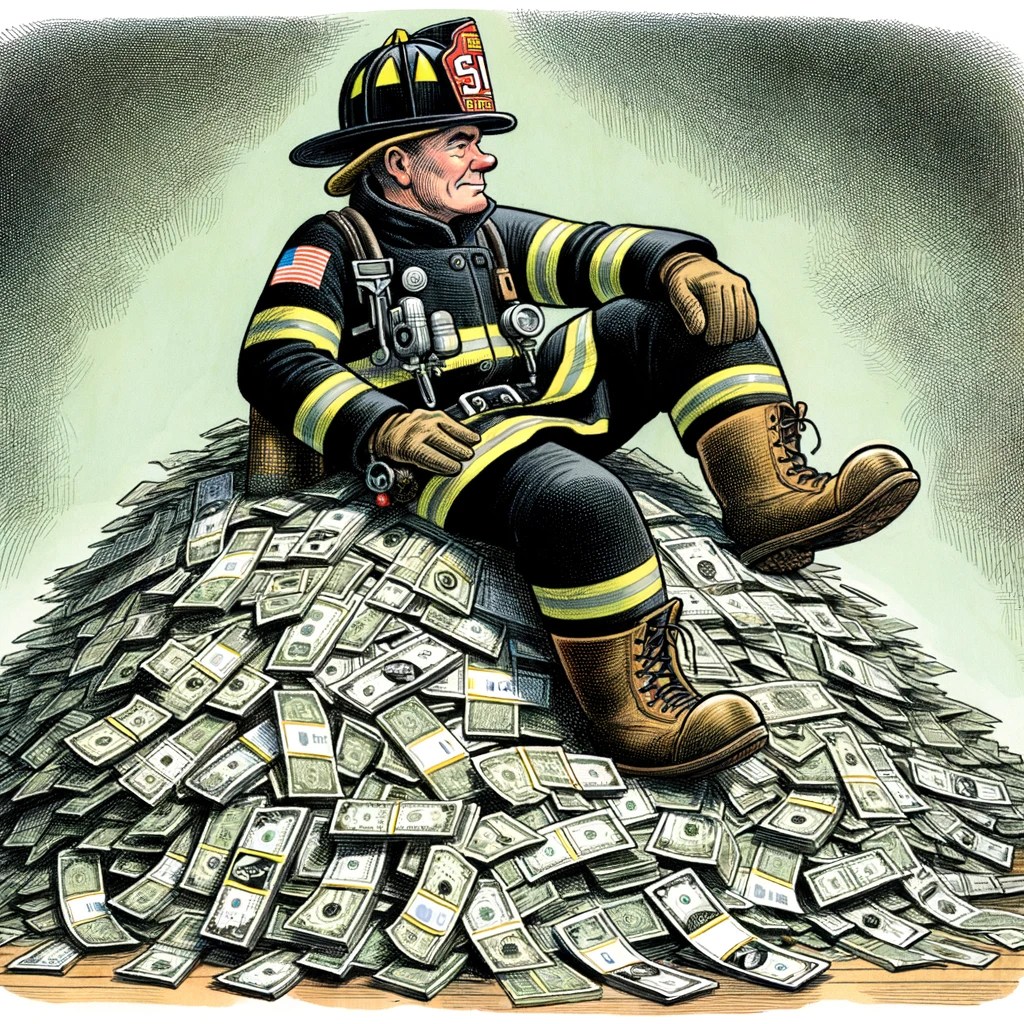

These Fees Would Be Unnecessary if Firefighters Weren’t Massively Overpaid

The first fire departments were staffed by volunteers. In many California cities, firefighter compensation has spiraled far beyond what most taxpayers earn. It’s common for rank-and-file firefighters to earn over $200,000 a year when you include base pay, overtime, and benefits. Many retire in their 50s with six-figure pensions, guaranteed for life and often adjusted upward for inflation. Excessive overtime is routine, not because of emergency need, but because of structural staffing policies and union contracts that incentivize costly scheduling.

For example, the average firefighter salary in San Jose, where the fees were just implemented, is $205,312 per year. Maximillian Duenas, a fire captain, made $703,815.29 in 2023. He was the highest-paid employee of the city of San Jose. The second highest paid was Galvin Charekian, also a fire captain, who made $588,301.93, including $309,358 in overtime, almost double his regular pay.

To put Captain Duenas’s mammoth paycheck in context, the average annual salary for an elementary school teacher in San Jose is approximately $83,416. Dividing Captain Duenas’s earnings by this average salary suggests that the city could employ about 8.4 elementary school teachers for the same amount. That is enough to teach 240 children for a year. $703,815 is also enough to buy 28,152 new books at $25 each, enough to fill an entire public school library. If the average annual maintenance cost per acre of a public park is $5,000, Captain Duenas’s salary could maintain approximately 140 acres of public parkland for a year. It’s also enough to repair 2,346 potholes assuming a range of $100 to $500 per pothole.

These costs aren’t the unavoidable price of public safety. They are the result of decades of political deals, union leverage, and a system that pays public employees more than the taxpayers who fund them. Now, when budgets strain under those inflated payrolls, departments propose slapping a fee on people at their most vulnerable moments — after an accident, injury, or medical emergency — to cover costs that are bloated by public employee compensation.

Notes

San Jose’s Fire Department recently protested their salaries, demanding more pay.

LAFD union chief made $540,000 in 2024 because of overtime.