“Some paradox of our nature leads us, when once we have made our fellow men the objects of our enlightened interest, to go on to make them the objects of our pity, then of our wisdom, ultimately of our coercion.”

(Trilling, Manners, Morals, and the Novel in The Kenyon Review (Ransom edit., Winter 1948) pp. 11-27.)

Trilling and the Prosecutor

This line, quoted in Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem, immediately jumped out at me as a commentary on the role of a prosecutor in reforming the criminal defendant. Certainly, coercion is at the heart of the criminal law. The moral prosecutor makes a judgment on the conduct of the defendant when he is deciding whether to file charges. Of course, the filing procedure’s main inquiry is whether the case can be proved. But there is always a more fundamental analysis about whether the conduct was morally wrong. Jean Valjean, in the Victor Hugo novel, was imprisoned for stealing bread to feed his family. Modern prosecutors abhor this anecdote and would never want to be involved in something like that. So at the start of every case we have an “enlightened interest” in correcting the morally wrong behavior of the criminal.

Criminals don’t exist in a vacuum. Every serious criminal case comes with a report on the defendant’s social background, with an opportunity for a defense lawyer to say the criminal is himself a victim of a poor upbringing, of drug or alcohol abuse, of problems at school, of neighborhood gangs, the list goes on an on. So enlightened interest changes to pity, following Trilling’s path.

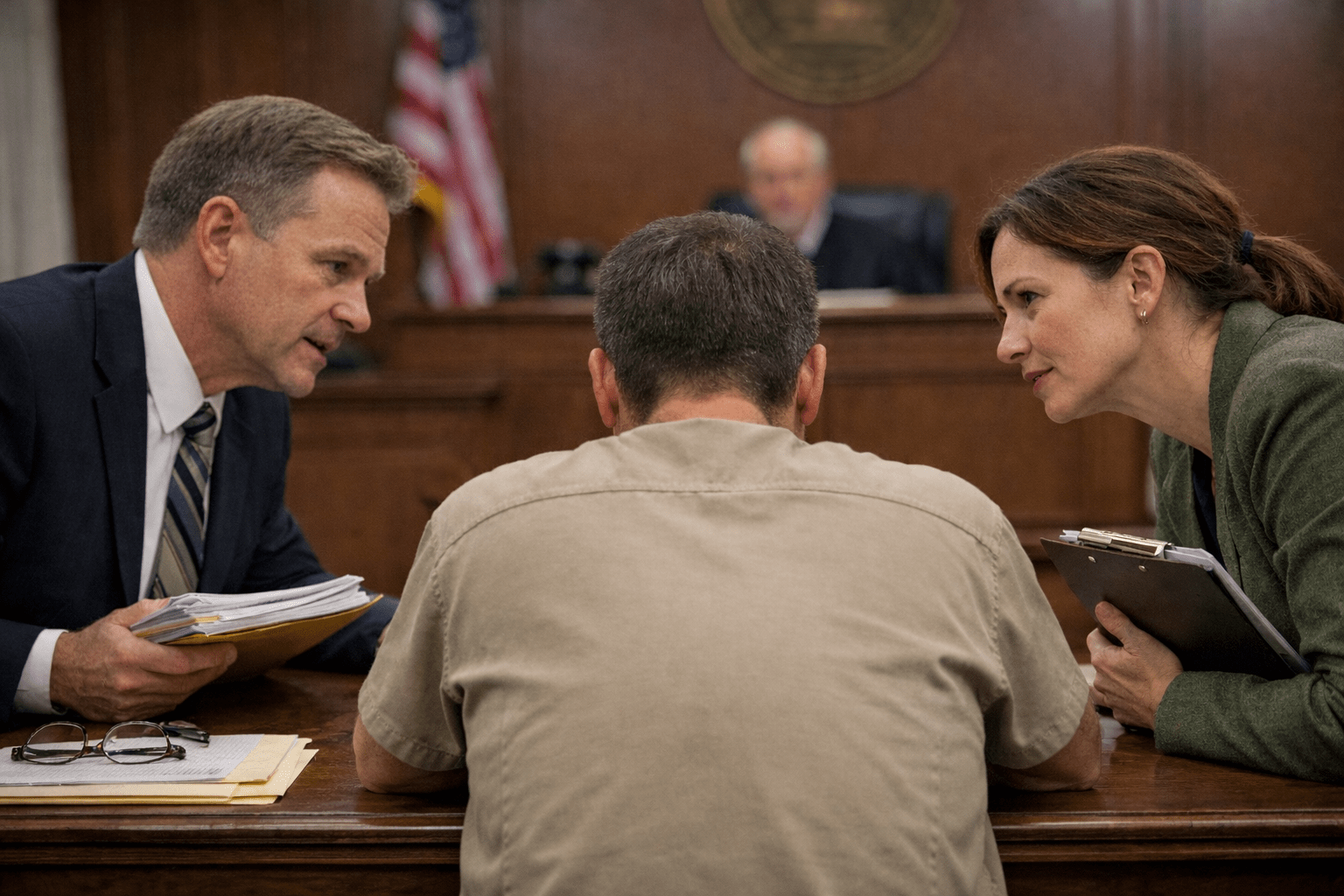

The prosecutor and the defense lawyer, with the slight involvement of the judge, come up with a plan to fix the defendant. He will be given substance abuse classes, he will attend the hospital and morgue program, he will do 200 hours of community service. If he is truly dangerous, he will “program” in prison, which provides enough of these services to occupy his entire prison day. The lawyers involved use their wisdom to protect the public and “rehabilitate” the defendant. Each lawyer has the confidence that he is entitled to design another person’s life, after all, look what a mess the defendant has made of it.

Most experienced practitioners understand what criminologists have known for years: the system cannot rehabilitate someone who does not want to rehabilitate themselves. And the vast majority of criminal defendants do not want to rehabilitate themselves. That is why the recidivism rates are so bleak. Criminal defendants, for the most part, don’t change, they just get too old to live the life of crime they continue to choose. So they must be coerced into changing. They must be threatened to complete their programs. They must be locked up where they are not tempted by the street. They must be supervised on probation and parole, which should be revoked if they do not comply with the rules. Again, Trilling’s framework admirably tracks reality.

These were my thoughts as I read Didion on a warm Sunday morning in February. I felt uncomfortable, I entertained doubts that my work might be paternalistic and that my wisdom was inadequate. Who was I to use the awful power of the law to meddle in another person’s life? I can barely get my kids into bed on time. I heard, in the accusing voice of the public defender’s office, that this was wrong.

Trilling and the Public Defender

Trilling’s quote is usually deployed against institutions that can force people to change, so it naturally lands on prosecutors, courts, prisons, and the police. But it occurred to me that now, more than ever, the role of the public defender has taken on the paternalism traditionally ascribed to the prosecutor. And not in the traditional sense that a public defender is himself part of the criminal justice system and advances its ends. But in the sense that a public defenders’ interest can turn to pity, which leads to the application of wisdom by coercion, this time in a more subtle way.

Public defenders have big hearts and often deeply moralistic views. Many believe their clients are victims themselves, of an unjust system, and that they have a moral duty to help them fight that system. A good public defender is often as much a social worker as a criminal lawyer. Sure, they have to craft a legal defense, but so many cases are resolved by plea bargain that often an appeal for a reduced sentence comes with an appeal that the client is in need of services rather than prison. That, in turn, requires an evaluation of the defendant as person, including their social history.

The evaluation of a defendant is explicitly required by laws providing for mental health diversion, the criminal justice system’s modern “get out of jail free” card. Evaluation is also prudent during sentencing, when the court can consider factors in mitigation related to the defendant’s history. Indeed, our system as a whole has been moving away from “equal justice under law,” where each defendant gets the same punishment for the same crime, to what might be described as a “doctor-patient” model, where the defendant gets what he needs to be “cured” of his criminal tendencies, regardless of whether it fits the crime. It seems to me, working with and speaking to public defenders all the time, that many of them are motivated by the enlightened interest to cure their patients.

Of course, once the defense lawyer finds out about the life of their client, they are likely to feel the same type of pity that a prosecutor would, perhaps more acutely, if generalizations about the public defense bar are true. The client is a product of their environment, never had a real chance, did what they had to do to survive, etc. These types of descriptions undermine the idea that the client is a right-bearing adult whose decisions matter, for better or worse. Once the pathological mindset takes over, the decision to commit the crime is an expression of the pathology, not an independent moral decision that has consequences. If the crime can be written off as “not a real choice,” then many other choices can be written off as well.

That’s where pity turns to wisdom. The defendant’s choices about trial tactics should take second place to the public defender’s wisdom. Their decision to admit the crime, for example, is unwise, because the public defender can get them off. Their decision to insist they are sane can be written off because an insanity plea would work better. Perhaps the most common example is overriding a client’s decision that they don’t need to go to rehab. The public defender, acting as social worker, believes that they know better.

Finally, coercion. Public defenders do not send anyone to jail, at least not alone, but they shape the client’s perceived options under pressure. Fear is a form of coercion, and it is used when clients are told that they will lose at trial if the lawyer is not allowed to take over. The client depends on the lawyer’s legal expertise, and their knowledge of how the system really behaves. The public defender knows about judges, probation, programs, collateral consequences, and can appraise the odds. Other forms of coercion are more direct. A public defender can pause a case and refer a client for mental health treatment by telling the court that the client’s conversation with the defender are not rational. This can lead to more time behind bars than a defendant would otherwise serve. There is no recourse, since public defenders essentially cannot be fired by their clients.

Some decisions are explicitly forced on the client. The line of cases involving McCoy v. Louisiana (2018) 584 U.S. 414 offer a list of choices that a lawyer can make for a client, even if the client later wishes counsel had done otherwise. Although a defense lawyer may not concede guilt when a client wishes to claim innocence, many other lesser decisions are taken away from the criminal defendant.

Conclusion

Even our most generous moral impulses have a built in hazard. The desire to help can curdle into paternalism, and when our evidently helpful advice is ignored, it is only one small step to forcing someone to change “for their own benefit.” Force is used with only the minimal amount of reflection, because after all, we mean well. The wrong question is the only one asked: “will this help?” instead of “should I force someone else to do this for their own benefit?” And lurking in the background is the specter that our own virtuous meddling is a mask for our desire to control.

Perhaps those of us in the system should be careful not to excuse our choices, and our coercion, with the thought that we mean well. After all, feeling strongly about what someone needs is not the same as being entitled to force them.