I read The Anatomy of Violence by Adrian Raine, all 373 pages, for the trivia. The book was interesting enough by itself, but the most engaging part of the book, and the reason I kept reading, was the little criminological factoids sprinkled throughout. You are more likely to be killed on they day you are born than any other day. Stepfathers are much more likely to murder their children than biological fathers. Men are better able to detect infidelity than women. Men who murder are more likely to be single. You are more likely to be killed in your home by someone you know than by a stranger. On and on. The longer your ring finger relative to your index finger, the more testosterone in your body. Yes, the crime-stopping effects of Omega-3 fish oil are interesting, but just not enough without the trivia.

I picked up an electronic sample of the first few chapters to read while waiting around in court. I followed Raines’ argument (a recitation of Dawkins’ selfish gene theory) but I was most interested the little facts and statistics he flavored it with. I kept telling other lawyers about them. By the time I was carpooling home, I had noted ten of the best and was going through them.

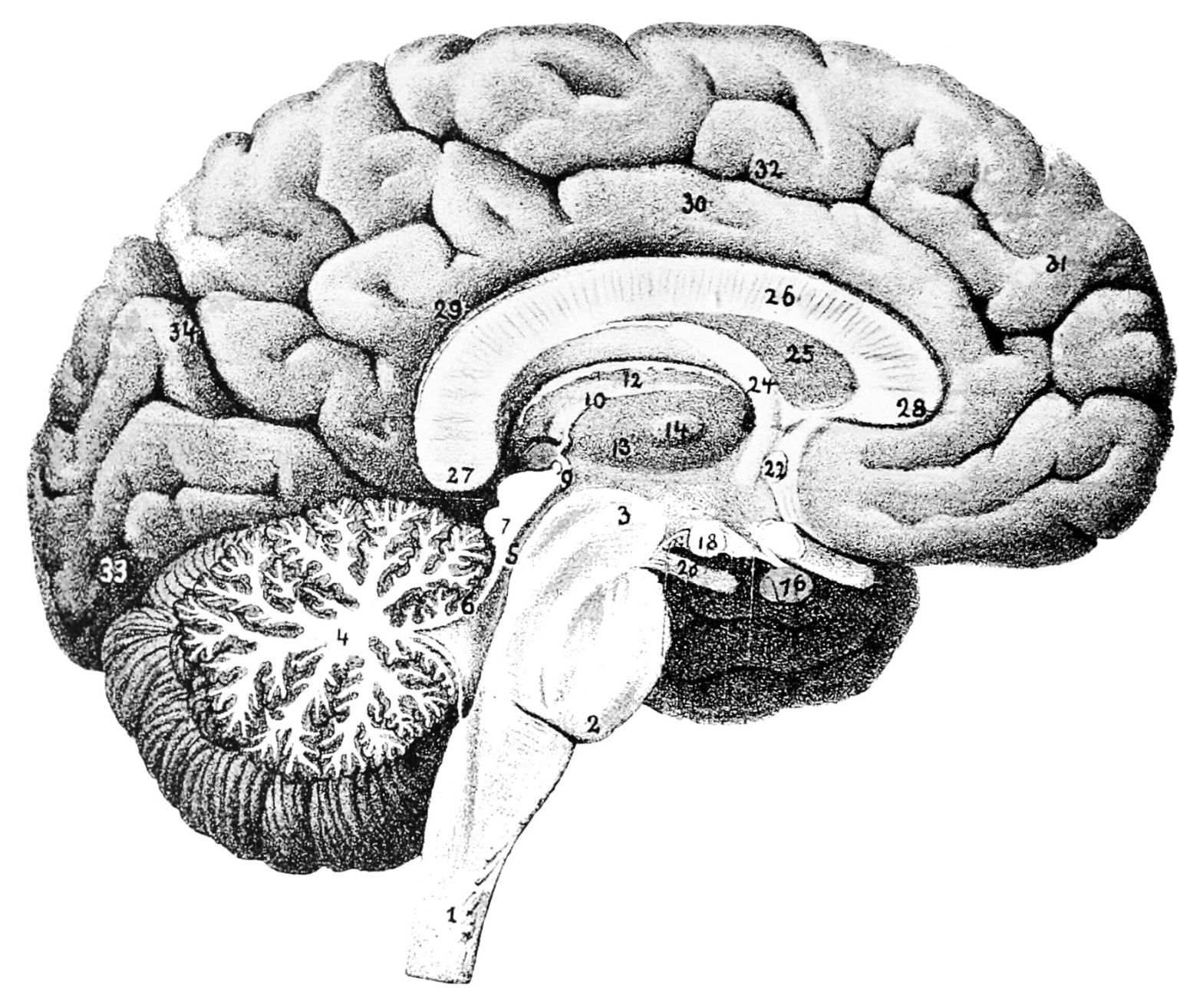

Raines clearly set out to write a book that was accessible to general readers. His book is peppered with examples of killers, serial or otherwise. His prose is lofty and often hyperbolic, which is totally necessary when you are talking about the left ventral prefontal cortex. Otherwise your eyes would dry up. And Raine even talks directly to the reader at times, speculating about why they bought the book and whether their purchase was predetermined by their biology.

Raine’s work on early childhood development is another area where the book really shines. He identifies things that can happen in the womb and in the first years of a child’s life that will increase the chances of criminality later on down the line. Head injury has to be at the top of the list. Maternal rejection, or just bad parenting during the first months, is another huge factor. Birth complications like hypoxia, preeclampsia, and maternal infection can all lead to neurological problems and then on to violence. Shaking your baby, failing to feed your baby, the list goes on and on.

It would be pretty uncontroversial to say that we should focus public policy on avoiding these problems. Parenting classes, better obstetrics, and safer playgrounds are all areas of improvement that would probably get wide agreement. But what about the implications or Raines’ work on the biological factors predisposing someone towards crime?

If the government finds out that someone is biologically predisposed to crime, should it label them and treat them differently? Maybe we should surveil them constantly. Maybe we should forbid them from having children, or force them to get a license. Maybe we should lock them up for our protection? Raines, originally from the UK, may not know that we have “Equal Justice Under Law” written above our Supreme Court. He does seem to know that many of these ideas are an anathema to the politically liberal. So he flirts with these ideas rather than marrying them. Even though his whole book is built around the idea that there are biological markers for violence, Raine is not willing to recommend that we do anything about it. Reading this book is kind of like reading about boat design by an author who doesn’t recommend sailing.

At the end of his book, Raine recommend that we treat violence as a public health problem. In my view, this approach ignores the moral aspects of crime, which would have a real, measurable effect on the crime rates. Crimes are crimes, not symptoms. Crimes are voluntary acts, not involuntary results of an unwanted disorder. We may learn a lot from Raines’ book, and take many of his suggestions, without medicalising crime.

Annotations

The Nazis were in favor of sterilization to prevent “unsound progeny”.

This farrago of pseudoscience written by a criminologist is everything that’s wrong with “evolutionary” theories about human behavior wrapped up and deposited between two covers. Jam-packed with dubious speculation based on misperceptions of how evolution works, “Anatomy of Violence” is all the more alarming because Raine seems to think the ideas in it ought to have a role in public policy. Not just a bad book, but a potentially dangerous one.

-Laura Miller in Salon.