In 1998, a young Slate reporter serving jury duty followed the law. He listened to what the judge told him about accomplice liability, and even though he didn’t like it, he correctly applied it to the facts and returned a conviction. Now that reporter, Seth Stevenson, feels bad for the defendant he convicted and wrote a long piece about it.

Stevenson Doesn’t Understand How Juries Work

Throughout the story, Stevenson tries to tell himself that he is not responsible for the lengthy sentence the accomplice is serving. He says that he was boxed in by the judge’s instruction, pressured along by the other jurors, etc. In his heart, however, Stevenson feels that he is responsible, because he voted to convict. Stevenson is right to think that he is responsible, he just doesn’t understand why. Stevenson should not misunderstand anything because, as he points out, he is a veteran reporter who has covered many trials. But he never seems to have learned the role of the jury. Nor does he understand basic facts about the way our government works and how they apply to his situation. Let me explain.

The role of the prosecutor is to present evidence proving a defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. The role of the jury is to decide what the facts are. In other words, the jury must decide if the prosecutor proved that the crime happened. The legislature decides what the law is. The role of the judge is to determine what law applies to the case. The judge explains the law to the jurors, who take an oath to follow the law. When a defendant is convicted, the judge must decide what sentence the law requires.

Stevenson is responsible for the sentence given to his defendant, but not in the way that he thinks. He thinks that he is responsible as a juror who voted to convict. As anyone with even a passing familiarity with the courts should know, this is not the case. Juries are specifically instructed not to consider punishment. That’s because, as noted above, their role is only to decide what happened. The judge then gets to decide the sentence. Defendants should not be acquitted because jurors don’t want them to face stiff consequences. Nor should they be convicted because jurors don’t like them, and want them to pay for being a bad person. Yet Stevenson continually falls into this trap. He says he was “searching for some way to grant him [the defendant] mercy.” Another juror said Stevenson “wanted to give [defendant] a break.” This is not a juror’s job, it’s the judge’s job. And ultimately, the legislature must decide what kind of breaks are available and to whom.

That’s where responsibility lies. Stevenson, and all other DC residents, voted on the laws that applied on the night of the crime. Stevenson’s representatives approved the sentence range that the defendant faced. Crucially, the legislature approved the accomplice liability laws that Stevenson disagrees with. The judge applied them. Stevenson, as well as the rest of us, are therefore responsible for the application of laws that we approve.

You Can’t Pick and Choose the Laws to Follow

Stevenson does not agree with the laws regarding accomplice liability. He’s not alone. Appellate courts also disagree with the doctrine of natural and probable consequences. That’s led to some big changes here in California. Nevertheless, it was the state of the law at the time of Stevenson’s trial. His disagreement with the law doesn’t mean he can ignore it. This may sound basic, but in a democracy we agree to follow laws that we disagree with. A senator can vote to legalize bazookas, but until the law changes, he cannot own one. Similarly, jurors may disagree with laws regarding accomplice liability, but they must apply those laws until they are changed.

This is something that Stevenson, and many others, don’t seem to agree with. I’ve met jurors who voice similar opinions. They think that they should only have to follow laws that they agree with, because their conscience is the ultimate law. This has the patina of reasonableness, but anyone who thinks seriously about it must reject this idea as unworkable. After all, the shooter in Stevenson case could just as easily say that he believes he should be allowed to kill over parking disputes (which he did), and he must be free to follow his conscience. We agree to constraints on our freedom to do things like this because we recognize the benefits that come with constraining the freedom of others to do things like this to us.

Sympathy for the Devil

It always shocks me that it’s the defendant that people feel sympathy for. The victim in this case, an off-duty police officer, had a wife and two children that he was caring for. The children were 3 and 4 months old at the time of the officer’s death. The defendant, who was 17, had a son that he was not caring for. Immediately before the murder, he was sitting on a stoop getting high with a gun. The contrast between these two men could not be more sharp. Yet part of me wonders whether Stevenson would feel as guilty for the victim after an acquittal as he does for the defendant after a conviction.

Stevenson needs a civics lesson, that much seems pretty clear, but that doesn’t mean he is bad person. It is natural to feel sympathy for others, crucial even. And he had to sit and see the defendant, face to face, in court for days. He had to discuss the defendants fate, think about his life, imagine the consequences for the defendant. These are things Stevenson did not have to do for the victim. The murder victim’s chair is empty. He doesn’t have to sit and look at the widow, the infant child, the four year old that were left behind. He doesn’t have to debate what is fair for them. So Stevenson, and too many others, let the victim remain in the grave, and direct all their sympathy to defendants. That’s what bothers me.

What Actually Happened

Judge for yourself whether the defendant did something wrong. The accomplice was hanging out, drinking, and smoking weed on a porch. It was 10 p.m. on a Saturday night. The accomplice was not with his infant child, even though he himself was only 17. The principal got into an argument with two men who had double-parked. The principal told the accomplice that he wanted to “‘smash’ the dudes.” The accomplice took his gun. A third man waited in the car as a getaway driver. The principal and accomplice stood at the top of a road and fired down at two men. We don’t know who shot, but Stevenson assumes the accomplice did not. After the shooting, all the men returned to the car together and drove off. No one reported the crime to the police. The accomplice and the driver eventually fled the state to avoid apprehension. Stevenson does not specifically say, but it appears that the accomplice ditched his gun. Another key fact that Stevenson will not say, but does allude to, is that the accomplice was heavily involved in prison violence after his incarceration. He was so dangerous that a succession of wardens at different institutions deemed the accomplice to dangerous to meet Stevenson face to face, and the accomplice was stabbed 10 times in custody, for reasons that Stevenson never shares.

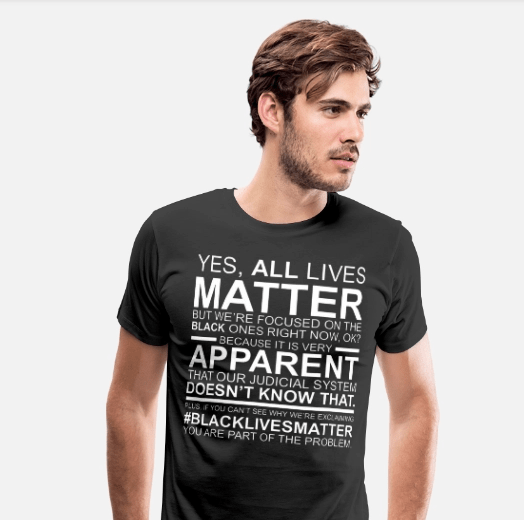

The System Isn’t Racist

Stevenson also casually mentions that the system is racist. He describes the criminal justice system “as an enormous machine – one designed to convey young black men into prisons and keep them there.” His defendant was “another shit-out-of-luck black kid from Northeast who’d made some bad decisions.” Who designed the system? Some mysterious cabal of racists in a dark room with a flowchart and a plan to discriminate against black people? The mayor at the time of the crime, Marion Berry, was black, like every mayor of DC since the creation of the office. The police chief in 1998 was black. The US attorney (the prosecutor’s boss) was black. African Americans have been the city’s largest ethnic group since the 1950s. The defendants were both black and so were both victims. Stevenson casually charges these people with a massive conspiracy against their own self-interest. There is no such conspiracy. The system isn’t racist.

What Jurors Like Seth Stevenson Should Know

You have to follow the law. For two reasons. First, that’s the way democracy works: we follow the law even when we disagree with it. Second, you take an oath to follow the law at the beginning of jury duty. Failing to follow the law is also breaking your solemn promise.

Leave sentencing to the judge. That’s their most important duty, after ensuring that the trial process is legally correct. Leave the setting of punishments to the legislature. Stevenson’s main problem seems to be that his defendant got a harsh sentence. Instead of putting the blame on the jury, who just did their job, he should blame the legislature. They made the decision, not him, about how long to incarcerate a cop-killing accomplice.