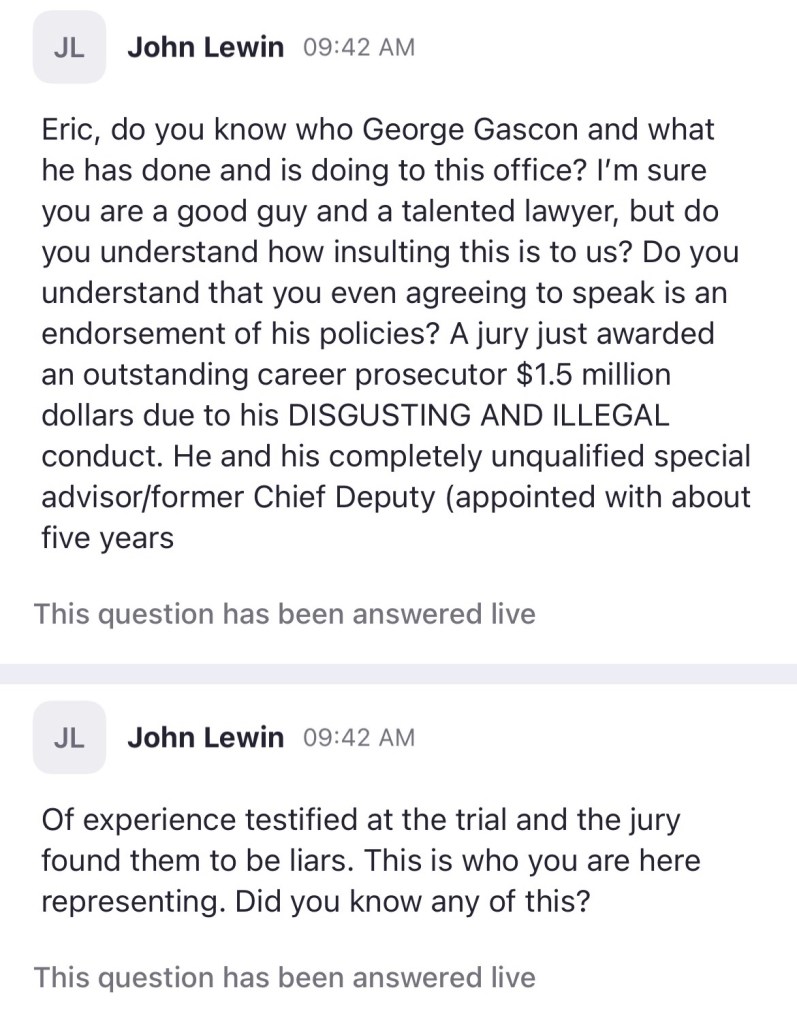

DDA John Lewin appeared on Instagram with eight pointed questions for Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascon. Lewin raised some tough questions, especially considering that Gascon awarded Lewin prosecutor of the year and then, in a dramatic turn, banished him to an obscure corner of the office. So take a tour through some of Gascon’s biggest scandals, or sit back and enjoy watching LADA’s cold case expert take on his boss, lawyer who has never tried a case.

The Questions

Here, Lewin is referring to Gascon’s indictment of Torrance Police Department officers Anthony Chavez and Matthew Concannon for the fatal shooting of Christopher Mitchell. The officers shot Mitchell during a traffic stop after he refused to exit his vehicle and reached for a gun in his lap. The gun was an air rifle.

Although LADA had already reviewed the shooting and found it justified, Gascon indicted the two officers in March 2023.

Rumors have been swirling that the indictment was based on a law that was not in effect when the crime was committed. Both officers are charged with voluntary manslaughter. The indictment is based on the argument that the force used on Mitchell was not necessary since the gun was only an air rifle. This theory would work under the current state of the law. (Pen. Code, § 835a.) Today, peace officers may “use deadly force only when necessary in defense of human life.” (Id.) Section 835a also toughened several other standards around the use of force by police officers. For example, the standard is now objective; it no longer matters whether the officers subjectively though that deadly force was necessary. Today, the officers will have a harder time defending themselves by saying they thought the air rifle was a real gun. However, at the time of the crime, the law was less strict. Back then, the standard was subjective. “I thought the gun was real” was a defense when this shooting happened. And back then the force used by police only had to be “reasonable,” not “necessary.”

Why is this a problem for Gascon? He’s trying to use the new law to prosecute the old shooting. You can’t do that. The law that applies to the shooting is the law in place at the time of the shooting, not today’s laws. Trying to use today’s laws to punish yesterday’s crimes is called an “ex post facto” law. These type of laws were banned by the Constitution. This ban is taught as a basic fundamental feature of American criminal law. Observers, especially prosecutors, have been shocked that Gascon made such a basic error.

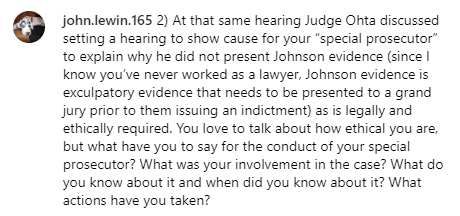

Questions about the Mitchell shooting continue. Lewin is referring to the rumor that Gascon special prosecutor Lawrence Middleton failed to present exculpatory evidence to the grand jury. This is required in state court but not in federal court. Many have speculated that Middleton was not aware of the rule requiring him to present exculpatory evidence because he only practiced in federal court where the rule does not apply. The rule requiring exculpatory evidence, called the Johnson rule, is universally known among Gascon’s deputies, making Middleton’s blunder especially embarrassing. (See People v. Johnson (1975) 15 Cal.3d 248.) It has been on the books for 48 years. Even worse, Middleton is being paid 1.5 million dollars a year and still making basic mistakes. Gascon’s office is full of prosecutors making $200,000 a year who have no problem obtaining indictments without violating state law. This bungled indictment is the only criminal charge Middleton has filed in the two years he has been on the payroll.

Lewin is referring to Gascon’s statements during an April 2023 news conference on the Mitchell shooting. “From my own personal review, I question whether the officers were able to see the gun before the shooting.” Gascon said. He continued “we know even the prior review indicated that there was no evidence that [Mitchell] was reaching for a gun.” The statements are significant to Lewin and many others because they seem to violate the State Bar’s Rules of Professional Conduct. Specifically, Rule 5-120 governs “Trial Publicity” and provides:

A member who is participating or has participated in the investigation or litigation of a matter shall not make an extrajudicial statement that a reasonable person would expect to be disseminated by means of public communication if the member knows or reasonably should know that it will have a substantial likelihood of materially prejudicing an adjudicative proceeding in the matter.

In other words, don’t talk about ongoing cases in the press, especially if it a potential juror may hear you. This rule explicitly applies to prosecutors. As with Middleton, it is likely that Gascon, who has never tried a case, much less a media case, simply did not know what his ethical obligations are.

Here, Lewin correctly points out that if the officers shot Mitchell without seeing the gun they would be guilty of first or second degree murder, not manslaughter. The theory of imperfect self-defense (“I thought he had a real gun but I was wrong”) would reduce murder to manslaughter. But only if a jury believes that the officers really thought he had a gun. If Gascon is right, and the officers shot him without seeing a gun, imperfect self-defense is not available and the right charge is murder. Although Lewin focuses his fire on Gascon, this is an equally valid question for Middleton, his special prosecutor.

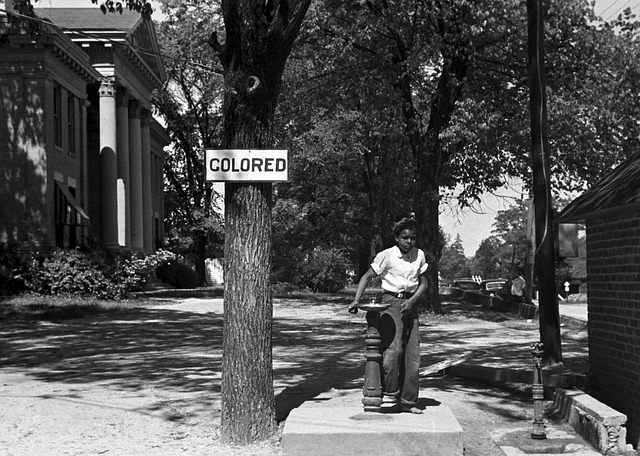

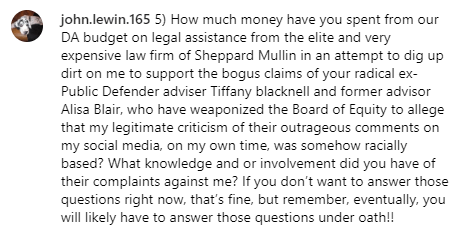

Gascon demoted Lewin and other experienced prosecutors when he took office. Two of Gascon’s top deputies (both former public defenders) filed equity complaints against Lewin based on his social media posts. The office hired white-shoe law firm Sheppard Mullin to investigate Lewin for equity violations. Many, including Lewin, believe this was done in retaliation for their criticisms of Gascon’s policies. At least 10 high-ranking members of the district attorney’s staff have filed lawsuits alleging they were removed from their positions because they voiced disagreement with Gascon’s policies. Gascon has also weaponized the County’s Equity Policy to suspend prosecutors who have been critical of him. Lewin’s comments could be an indication that Gascon is using the same tactics against him.

Lewin is referring to Gascon’s practice of taking credit for his deputies’ convictions. For example, Eric Holder Jr. murdered rapper Nipsey Hussle. Holder was convicted by DDA John McKinney, a veteran prosecutor who has been critical of Gascon. The press release celebrating the conviction completely omitted McKinney, who did all the work.

Shawn Randolph, who is also mentioned by Lewin, won 1.5 million dollars after Gascon retailed against her. She proved that Gascon demoted her because she pointed out that some of his policies were illegal.

Joseph Iniguez, a four-trial prosecutor, jumped the line to Chief of Staff after endorsing Gascon during his campaign. Iniguez was arrested for being drunk in public at a fast food drive-thru. Although the police did not press charges, Iniguez sued the officer for impeding him as he attempted to videotape the encounter. Iniguez says he captured the entire incident on video. He also claims that the video proves the police officer made an illegal arrest and lied about it. Iniguez has never released the video even as the allegedly dirty officer has continued to do his job and make arrests. This is a problem.

If Iniguez is telling the truth, his failure to release the video has allowed a dirty, dishonest cop to remain on the beat. That’s a violation of his obligation as a prosecutor to provide defendants with evidence they may need. Specifically, if you were arrested by this officer, you could hold up Iniguez’s video and say, “this officer is a liar.” You could do that if you had the video, which you don’t, because Iniguez won’t produce it. If, on the other hand, Iniguez is lying about the officer, who really did nothing wrong, then Iniguez’s actions makes sense. He doesn’t want the world to know he’s lying.

When Gascon came into office, he gave a sweetheart offer to a criminal represented by a campaign donor. Moreover, the offer was negotiated for Gascon by Tiffany Blacknell, a public defender. That means that Blacknell was negotiating for Gascon while working against Gascon on behalf of the defendant in this case. This is an obvious conflict of interest. Although this was a particularly egregious example, prosecutors have noticed many others.

The largest apparent conflict was Gascon’s decision to allow his policies, like his ban on the use of any enhancements, to be written by public defenders. In other words, the criminal defense bar got to write policies that benefited their clients at the expense of the public, who wasn’t even at the table.

Do The Answers Matter?

George Gascon began his career as the District Attorney of San Francisco County. He could easily fire prosecutors he didn’t like in San Francisco. But the rules are different in Los Angeles. It is much harder, if not impossible, to fire John Lewin, which gives Lewin the freedom to ask these hard questions. You can tell that Lewin is angry by the tone of the questions. The most important question of all is whether Los Angeles is angry enough to oust Gascon in 2024.